Guidance on the Consideration of Defence Representation Order Applications.

1. INTRODUCTION

1. During 2008 the then Legal Services Commission in conjunction with Her Majesty’s Court Service held a number of workshops to assess current practices and training needs surrounding interests of justice decision-making for the grant of criminal legal aid. Following the workshops a meeting of experts was held to discuss ways in which greater certainty could be introduced.1

2. Guidance issued then was the outcome of that process. Its aim was to improve the quality and consistency of decision-making. Whilst it is addressed to and written primarily for LAA staff that grant and refuse legal aid, it will also assist applicants and their solicitors.

3. Following discussions with Representative Bodies the guidance has been amended further in 2018 to provide clarity on a number of issues.

4. This revised guidance is national guidance by the Legal Aid Agency. It replaces all other guidance and should be followed by LAA staff, Providers and applicants alike. All other guidance, whether national or local, should be disregarded.

1 HMCTS and the LAA would also like to acknowledge the advice and assistance of Professor Richard Young of the University of Bristol in the preparation of this guidance.

2. GENERAL PRINCIPLES

1. Criminal legal aid may be granted for proceedings before any court in favour of any individual accused or convicted of a criminal offence. Criminal legal aid also extends to other non-criminal proceedings, which include those set out in section 14 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act 2012 (e.g. proceedings in relation to a bindover or contempt of court) and certain ‘prescribed proceedings’ listed in regulations.2

2. Under the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act 2012 legal aid should, subject to means testing, be granted in cases only where it is in the interests of justice for the defendant to be represented. Each application for legal aid must be considered individually, and decision-makers must weigh up all the relevant factors.

3. A list of factors which must be taken into account (known as the Widgery criteria) are contained in Section 17(2) of the Act and these are reproduced on legal aid application forms. Decision-makers may consider additional factors not on this list, but they must be relevant to the interests of justice. Applicants must make clear on application forms the factors on which they are relying.

4. In some cases two or more factors may combine together to justify a decision to grant when neither by itself would have sufficed. When such a combination is relied upon, this should clearly be noted on the application form.

Providing sufficient information

5. It is the responsibility of the applicant, usually with the assistance of a solicitor, to provide sufficient relevant information to support an application. Where insufficient information is provided, the application should be refused (and be recorded as a refusal for statistical purposes) rather than returned. This should be communicated to the applicant who may wish to provide additional information. Whilst it is acknowledged that a need to re-apply may initially cause some delay and an increase in administration, it will also encourage applicants to provide sufficient information at the outset, resulting in longer term efficiency.

6. It should be remembered that the Legal Aid Agency does not have access to Police National Computer records or Court records. Nor do they know the client or his/her circumstances, they rely wholly on the information provided in the application.

For the avoidance of doubt the Legal Aid Agency will have no details of any previous convictions for the client, or any other details about the nature of the allegations other than that which is provided with the application.

Giving applicants the benefit of the doubt

7. If, after considering all the relevant factors the decision to grant is finely balanced, then the applicant should be given the benefit of the doubt and legal aid granted. This will apply only when there is enough detail on the application form for a competent decision to be taken. The benefit of the doubt should not be used to fill gaps in information which applicants should provide. It is not a requirement that a list of previous convictions be provided as these are often not available at the time the application is submitted. However, if reliance is placed upon previous convictions, it is important that sufficient information about them is given (i.e. approximate date, court, charge, sentence etc. See para 33 below).

Co-defendants

8. If a case involves co-defendants, the applicant should instruct the same solicitor as the co-defendant(s) unless there is, or is likely to be, a conflict of interest.3 The application form requires the applicant to state the reasons why he and his co-defendants cannot be represented by the same solicitor. The most common reasons are that one defendant is blaming the other or they are running incompatible defences (e.g. one says the fight never happened, the other says there was a fight, but he was defending himself).

Cases in the Crown Court

9. With the introduction of means testing in the Crown Court, the interests of justice test is automatically met in all cases which are committed, sent, or transferred to the Crown Court. In such cases, the interests of justice test is ‘Passported’ and these applications are subject to the means test only. There is one exception, being that of appeals to the Crown Court against conviction or sentence. Such applications should be subject to both the interests of justice test and the means test.

Equality of Arms

10. The principle of ‘equality of arms’ is important for Legal Aid, it refers to the legal principle that a defendant must have an effective opportunity to present his own case to the court under conditions which do not place him at a substantial disadvantage in relation to the prosecution.

11. The fact that the prosecution case will be presented by a professional prosecutor is not a good reason, in itself, to conclude that an unrepresented defendant is at a substantial disadvantage.4 The law governing criminal legal aid clearly envisages a class of cases which should not attract publicly funded legal representation. The issues (if any) in these cases will typically be narrow and straightforward enough such that any disadvantage to an unrepresented defendant would be less than substantial. Legal advisers in magistrates’ courts have a legal duty to assist unrepresented defendants.

Information available at the time that instructions are taken

12. A decision about whether legal aid is granted should take into account the situation known at the time of taking the instructions and not use the benefit of hindsight.

13. In cases where the hearing has concluded before the application has been determined, the outcome of the hearing should not be the deciding factor in assessing whether or not the interests of justice test is satisfied. If loss of liberty was likely at the outset then the application will have satisfied the test notwithstanding the fact that the defendant was released, perhaps as a result of the solicitor’s representations.

Role of the Legal Adviser

14. The primary role is to provide the magistrates with advice to assist them with their function and role. This includes questions of law and procedure, questions of mixed law and fact, penalties available and other issues relevant to the matter before court. A legal adviser has a duty to ensure that every case is conducted fairly and is also under a duty to assist unrepresented parties to present their case. They must do so without appearing to become an advocate for the party concerned and should not affect the granting of Legal Aid if the criteria are met. In addition to this at the stage of plea, a legal adviser will advise a defendant in respect of credit available for timely guilty pleas.

2 See Annex A. 3 Regulation 13 Criminal Legal Aid (determinations by courts and choice of representative) Regulations 2013. 4 In R v. Havering Juvenile Court ex parte Buckley, Lexis CO/554/83 12 July 1983 it was noted that the fact that the prosecution was legally represented was something that could properly be taken into account, but it did not follow that a grant of legal aid must be made in such circumstances.

3. GROUNDS FOR GRANTING LEGAL AID – THE WIDGERY CRITERIA

Under section 17 (2) of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 the following factors (sometimes referred to as the ‘Widgery Criteria’) must be considered:

3.1 It is likely that I will lose my liberty if any matter in the proceedings is

decided against me.

1. Loss of liberty does not just mean straightforward imprisonment, it also includes:

- Suspended custodial sentences

- Remands into custody or into secure accommodation

- Hospital orders and similar forms of confinement

- Committal to prison or suspended committal for non-payment of fines, council tax or maintenance.

2. Many applications rely on this as a reason for grant. It should be noted that the test requires that custody is ‘likely’. Where there is merely a ‘risk’ of custody, but custody is not likely, this does not meet the criteria.

3. Whilst a tag or curfew is certainly a restriction on liberty, generally community penalties (upon which a curfew is attached) don’t ordinarily constitute a loss of liberty. If, however, a tag is attached to a suspended sentence then this is a custodial sentence (see paragraph 3.1.1 above) and loss of liberty is made out. It is worth noting that if a tagged curfew is to be attached to a bail condition then it can only be done as a direct alternative to a remand in custody, but this does not relate directly to sentence. The possibility of a community order is something which may come into consideration under “any other reasons” when assessing the totality of an application.

Sentencing Guidelines

4. To make an accurate and reasoned decision on the likelihood of a loss of liberty, it is vital that the Magistrates’ Sentencing Guidelines published by the Sentencing Council are addressed.

5. The published guideline for the offence should be used to work out the starting point for sentencing. The likelihood of custody should be assessed taking into account the circumstances of the offence and any previous convictions. The applicant should provide enough information about the facts of the offence for the starting point to be identified, but some cases may not fit clearly into any category described in the guideline.

6. Every application must be considered individually. Applications relating to a particular charge or category of charges should not be automatically granted or refused without full and proper consideration.5 For example, attention should be drawn to the Domestic Abuse guidelines6 which came into force May 2018. These guidelines will be relevant in common assault cases, and confirms that whilst injuries may sometimes not be severe, if there is serious psychological harm, custody becomes likely (paragraph 13 of the guidelines). It also promotes an increased use of restraining orders (paragraph 20) which should be considered Notwithstanding this, a strong presumption of grant should operate in the following circumstances:

- The starting point in the guidelines is a custodial sentence.

- The defendant would be in breach of a suspended sentence if convicted, either through breach of its requirements or via the commission of a further offence.

- The defendant is before the court for a second or subsequent breach of the requirements of a community order (i.e. there is a previous breach of the order which was admitted or proved at court).

- The offence is imprisonable and occurred whilst the defendant was subject to recall in relation to a previous custodial sentence.

7. For cases outside these categories with a starting point lower than custody, the applicant should indicate the relevant sentencing starting point, which should be considered against the guidelines. The applicant must then identify the aggravating features peculiar to the offence and/or the defendant which

lead them to believe that despite the lower starting point, loss of liberty is likely.

8. The Imposition of Community and Custodial Sentence Guidelines7 also have some useful definitions of what a low/medium/high order entails and also criteria of when it is appropriate to suspend sentences.

9. In the case of McGhee8 the High Court rejected the argument that a community order with unpaid work constituted a loss of liberty. However, the possibility of such an order being imposed may be a contributory factor which, in combination with other factors, may justify grant (see ‘Any Other Reasons’ below).

10. Magistrates and District Judges MUST follow the guidelines or give their reasons if they seek to depart from them. Most aggravating and mitigating features will appear in the guideline but the list is not exhaustive.

11. An aggravating feature is something that makes a crime more serious, e.g. recent previous convictions for a similar offence or breaching a previous court order. Where a defendant relies on an aggravating factor they should give sufficient detail to justify how the case meets the IOJ test. For instance it would not be sufficient in a theft matter to state that the value of the alleged theft is ‘significant’, and the best estimate of value should be provided.

12. A mitigating feature is something that may reduce the sentence, e.g. provocation or remorse in respect of the offence or personal problems in respect of the defendant.

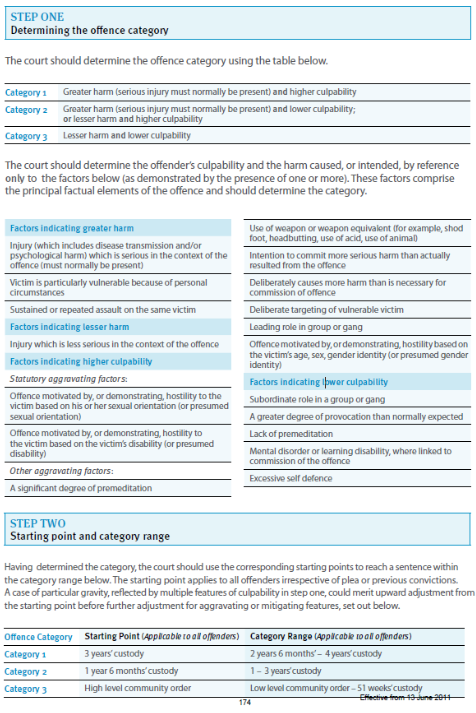

13. There are generally 2 styles of guideline available. (Fig 1 below shows the old style) Old style guidelines are more flexible and open to a greater degree of interpretation due to their simplicity.

5 R v. Highgate Justices ex parte Lewis, 142 JP 78.

6 https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/6.4143_SC_Domestic_Abuse_Paper_WEB.pdf

7 https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Definitive-Guideline-Imposition-of-CCS-final-web.pdf

8 R v. Liverpool City Justices ex parte McGhee (1993) Crim LR 609.

Fig 1 – Old Style (example only)

Guidelines

14. These guidelines require the user to find a “best fit” to the nature of offending with the facts of the case they are dealing with and then to place the offence into 1 of 3 categories. This provides the starting point and range of sentence.

15. Once the starting point has been established, the sentencing court will look at factors influencing the seriousness of the offence. This is a combination of culpability (level of wrongdoing) and harm (caused to the injured party or community). This can aggravate (left column) or mitigate, (right column).

16. This aggravation/mitigation allows the sentencing court to move around within their selected range dependent up the weight of the aggravation or mitigation. If the weight of the aggravation or mitigation is exceptional, then a sentencing court may depart from their guideline and go outside of their

range. This requires robust reasons bearing in mind the duty to follow the guidelines.

17. This is illustrated by offences like Obstruct PC and School Non‐Attendance, which can theoretically result in short terms of custody but the guideline does not afford the court this disposal. In addition a sentencing court would act unlawfully if they were to exceed the statutory maximum punishment for any particular offence. Please refer to paragraph 3.1.18 for an example of wide use of the range of the guidelines.

18. The statutory maximum sentence is displayed on the first page of each offence within the guidelines. Some offences do not carry a custodial sentence; and any offence which does not carry custody, can only be dealt with by way of a fine or a discharge.

19. An example is a repeat offender for shop theft, an offence which, in its simplest form would not ordinarily attract custody. Given an offender with a significant record, a departure from the guidelines may be appropriate and a custodial sentence likely. Some detail of the previous convictions, (not necessarily evidence) but details such as frequency, type of offending and recent disposals will assist in making this decision. The defendant’s solicitors may be supplied with a copy of the previous convictions as part of the Initial Details from the prosecution but this is not always the case given the short time between arrest and first hearing. An indication of the number, type, how recent the convictions were and what type of sentence was imposed should assist in making the legal aid decision. Attention should be drawn to the theft guidelines which state –

“In cases involving significant persistent offending, the community and custodial thresholds may be crossed even though the offence otherwise warrants a lesser sentence. Any custodial sentence must be kept to the necessary minimum”.

| Offence | Starting Point for sentence | Aggravating factors? |

| Theft from shop | Band B Fine | 35 previous convictions for dishonesty. Recent record of Shop Theft in similar circumstances – latest sentence was custody of 6 weeks, imposed 3 months ago. |

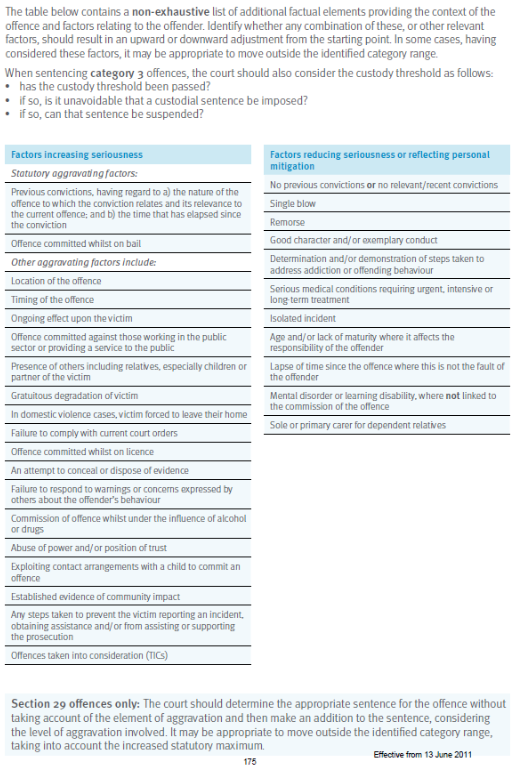

Fig 2 – New Style Guideline (example only)

20. This is the new style of guideline and it is more rigid in approach at step 1. Step 2 requires the application of the fixed list of examples to establish the category by looking at culpability and harm and is less rigid depending on any aggravating or mitigating circumstances.

21. Anything not in the lists of culpability and harm at step 1 are taken into account at step 2 as they can affect the seriousness of the offence.

22. Step 2 also provides a list but this is no more than a list of suggestions and anything can be taken into consideration here if it makes an offence more or less serious.

23. The combination of these factors of seriousness will allow a sentencing court to move within their category range, and if factors are sufficiently serious it may allow movement to a higher category of sentence. Again the court would usually need to be satisfied there was a good reason to move out of range.

Fig 3 – Example only

Serious Offences – Custody Always Likely

24. This is not an exhaustive list, but below are a selection of serious offences that are more likely to appear than others, and which are almost certainly likely to result in a custodial term.

25. Some of the offences below have a starting point short of custody but will usually attract custody with aggravating features and they are marked to this effect. Others are clearly over the custody threshold. If an offence is Indictable Only it is so serious that a magistrates’ court’s maximum penalty of

6 months custody is insufficient and it is sent to the Crown Court forthwith.

Violence

- S18 GBH ‐ Wounding with Intent (Indictable Only)

- S20 GBH – Malicious Wounding (Either Way)

- S47 ABH – Assault ‐ Actual Bodily Harm (Either Way) Look for aggravating features.

Dishonesty

- Robbery – (Indictable Only)

- Blackmail – (Indictable Only)

- Aggravated Burglary (Indictable Only)

- Domestic Burglary (Either Way)

- Domestic Burglary – 3rd Strike – (Indictable Only)

- Theft in Breach of Trust – (Either Way) Look for aggravating features.

Public Order

- Riot – (Indictable Only) Violent Disorder (Either Way)

- Affray (Either Way) – Look for aggravating features.

- 3.6

Sexual Offences

- Sexual Assault by Penetration (Indictable only)

- Sexual Assault of Child Under 13 (Either Way)

- Possession of Indecent Images of Children (Either Way)

- Sexual Assault (Either Way) – only the most minor forms of sexual assault (e.g. pinching a bottom) would not result in a custodial sentence

Drugs

- Possession of Class A ‐ Intent to Supply (Either Way)

- Possession of Class B ‐ Intent to Supply (Either Way) – Look for aggravating features

- Importation of Drugs (Either Way) Interest of Justice guidance May 2018 13

- Importation of Drugs – 3rd Strike (Indictable only)

Miscellaneous

- Conspiracy – (Indictable Only)

- Arson with Intent/Reckless to Endanger Life (Indictable Only)

- S4 Harassment ‐ Fear of Violence (Not the Public Order Offence)

Example 1

Defendant A has been charged with s18 wounding.

The offence is indictable only and is therefore very likely to result in a custodial sentence if guilty. The Interests of Justice Test would be passed in this instance.

Example 2

Defendant B has been charged with burglary of a commercial property (Theft Act 1968. s.9). The application notes that the defendant is alleged to have significantly damaged the property whilst making their entrance and threatened the office manager who was on the premises at the time.

The offence is either way with a sentencing range of a Band B fine to custody. The offence type alone does not mean that the Interests of Justice Test is passed as there is not necessarily a likelihood of custody, and the LAA should look at further information that is provided in this application. In this instance the damage alleged to have been caused by the defendant, the presence of a victim on the premises and the alleged threats made to them are factors indicting greater harm, and would make custody likely in this instance. The Interests of Justice Test would therefore be passed.

Example 3

Defendant C has been charged with cultivating cannabis. The application states that due to the number of plants and potential value the court will consider imposing a custodial sentence.

The offence is either way with a sentencing range of a medium level community order to custody. The offence type alone does not mean that the Interests of Justice Test is passed as there is not necessarily the likelihood of custody and the LAA should look at the further information that is provided in the application. For this offence the number of plants involved is pertinent to the sentencing category. Stating that there is a ‘number’ of plants is not specific enough to demonstrate that the criteria for IOJ is met.

Unusual Sentencing Exceptions

26. Some offences are more serious due to their prevalence and impact, as such, the sentencing guidelines are considered in a more serious light and the penalties imposed are greater.

Possession Bladed Article/Offensive Weapon

27. In the offensive weapon guideline, the starting point is given an uplift if the weapon has a blade (i.e. a knife) so the starting point (ordinarily high community penalty) increases to 12 weeks custody where the weapon has a blade. That being the case, all Bladed Article cases are likely to pass the custody threshold and many are sent to the Crown Court9.

28. Whereas the value of the metal can be relatively low, significant sentences can result. Applications may mention collateral damage. This is due to the fact that the loss suffered from metal theft is often disproportionate to the value of the goods taken. Consider thefts from railway property, or electric and network cabling as examples, and the danger, disruption and overall financial harm this creates. Similarly significant harm to the community can arise from targeting churches and war memorials.

9 https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Bladed-Article-Definitive-guideline_WEB.pdf

The Range of Sentences

29. Before a custodial sentence is passed, the court must be satisfied that ONLY CUSTODY IS APPROPRIATE. They must therefore be satisfied that nothing else will suffice. The main sentence range is set out below from bottom to top.

- Absolute Discharge

- Conditional Discharge

- Fine – Band A (50% of weekly net income)

- Fine – Band B (100% of weekly income)

- Fine ‐ Band C (150% of weekly income)

- Low Community Penalty

- Medium Community Penalty

- High Community Penalty

- Custody – Suspended or Immediate

Custody Due to Refusal of Bail

30. If an application states that a defendant is appearing in custody the LAA must first check whether this is police or court custody. If the defendant has been remanded into custody by the police then there is no presumption that the IOJ test is satisfied. If a court has remanded a defendant into custody then the interests of justice can be satisfied in relation to a loss of liberty as a result of the refusal of bail where the solicitor has explained the reasons for the remand.

Previous Convictions

31. The relevance of previous convictions depends upon how old they are, how serious they were, and how similar in character they are to the current charges. The court will generally take no notice of:

- spent convictions.

- cautions, warnings and reprimands.

32. A recent history of breaching court orders will make a custodial sentence more likely (provided that the new offence is punishable with imprisonment). Previous convictions will act as an aggravating factor when the court decides sentence. It will usually only be appropriate to take them into account if this means that a custodial sentence is likely. For example, previous convictions will be far less likely to aggravate the sentence to custody if the relevant sentencing guideline indicates the starting point for the sentence is a fine than if it is a high community order.

33. Previous convictions may also put a defendant at greater risk of conviction if they are pleading not guilty because the prosecution may be allowed to put the convictions in evidence.

34. Where recent convictions are relied upon, but they are of a totally different character to the current charges, the applicant should explain why these are relevant to the likelihood of custody in this instance.

The Legal Aid Agency has no access to PNC or court records and in relation to previous convictions relies solely on the information provided in the application. It is therefore important that the applicant provides as much information as possible about relevant previous convictions. Where the defence have access to the standard police form of recorded convictions they may attach this to the application as evidence. However these are frequently unavailable at the time of the legal aid application, and the defence may not have exact details of the previous convictions for their client. In this instance the defence should provide as much information as they have from their client and in particular:

- a description of the previous offences said to be relevant.

- the dates (or approximate dates) of conviction.

- the sentences imposed (which will generally indicate their relative seriousness).

35. Stating “Has relevant previous convictions” is not enough to satisfy the Interests of Justice criteria.

Example 1

Defendant A has been charged with s1 Theft from shop of approximate £1,000 value. The application gives no details of any aggravating factors and simply states that the defendant has ‘previous convictions’.

The offence type is either way with a sentencing range of a Band B fine to 2 years custody. The previous convictions will be an important factor in determining whether the case meets the Interests of Justice Test, but there is insufficient detail to demonstrate that the test is met.

Example 2

Defendant B has been charged with affray. The application gives no details of any aggravating factors but explains that the defendant has four previous convictions for violence in the last two years. The last of these was three months ago when the defendant received a custodial sentence of two months. Further specific information was not available to the solicitor at the time of instructions.

The offence attracts a sentencing range of a Band C fine to 12 weeks custody. Although no specific detail is given about the dates and offences there is sufficient detail provided to see that custody is likely for this defendant if

guilty.

Remands into Custody

36. Loss of liberty can also mean a remand into custody.

37. The fact that the defendant is appearing before the court in custody is not relevant. In these circumstances legal aid and legal representation will be justified only where it is likely that he will remain in custody after the hearing.

38. If the applicant believes that loss of liberty is likely due to a remand into custody then the application form should make clear:

- why the case is likely to be adjourned (without an adjournment there will be no remand at all).

- whether the prosecutor will oppose bail.

‘All options’ and custody band reports

39. The request for an all options report is good sentencing practice and in line with the Senior Presiding Judge’s guidance to allow a two-stage sentencing approach. The Bench who request a pre‐sentence report will probably not be the same who pass sentence as the case will be adjourned to a later date pending the preparation and delivery of the report. To leave all sentencing options open is to allow the court to pass any sentence the law allows. All options reports and custody band reports are the same. The probation service will look at all sentencing options, from discharge to custody.

40. Where the Bench requests an ‘all options’ sentencing report this does not necessarily mean that the IOJ test is met. It should be viewed as a good, albeit not absolute, indicator that custody is likely, but the sentencing guidelines should be referred to in all cases. The following should apply as a guide:

- Where the sentencing guidelines suggest that custody is likely given the nature of the offence and any aggravating factors disclosed on the application, then there is a strong presumption that the IOJ test is met.

- Where the sentencing guidelines do not suggest that custody is likely (for instance where they suggest that there is a broad range of sentencing options for the offence) the LAA should consider whether there is anything in the application to suggest that custody is likely to be imposed in this instance such as aggravating factors or previous convictions.

- Where the sentencing guidelines do not suggest that custody is likely and there’s nothing to suggest that custody will be imposed in this case (e.g. it’s a relatively minor offence and there no aggravating factors) then the application does not meet the IOJ.

- If, after considering all the relevant factors the decision to grant is finely balanced, then the applicant should be given the benefit of the doubt and legal aid granted. This will apply only when there is enough detail on the application form for a competent decision to be taken.

3.2 I have been given a sentence that is suspended or non-custodial. If I break

this, the court may be able to deal with me for the original offence.

1. The existence of the current suspended or non-custodial sentence must have some bearing on the current proceedings in order to be relevant to the interests of justice decision. The fact that the offence took place whilst the defendant was subject to a community order, for instance, is unlikely in itself to justify grant unless the wider circumstances of the case mean that loss of liberty is likely.

2. Whilst it is important that each case be considered on its individual merits, a strong presumption of grant should operate in the following circumstances:

- the defendant would be in breach of a suspended custodial sentence if convicted (either through the breach of its requirements, or via the commission of a further offence).

- the defendant is before the court for a second or subsequent breach of the requirements of a community order. (i.e. there is a previous breach of the order which was admitted or proved at court).

- the offence is imprisonable and occurred whilst the defendant was subject to a previous custodial sentence either before his release, or after release whilst subject to recall.

Breach of the Requirements of Community Orders

3. Applications should state:

- the number of previous breaches of the order

- whether revocation of the order is being sought by the probation service

4. An application for the first breach of a community order is very unlikely to be granted without an additional factor in the case which increases the likelihood of a custodial sentence, or presents some other reason to justify grant. For a second or subsequent breach a strong presumption of grant should operate as stated above under ‘Custodial Sentences’.

3.3 It is likely that I will lose my livelihood.

1. In almost all cases the defendant will need to be in employment (or self employment) in order to argue that his livelihood will be lost.

2. Legal aid should be granted only when:

- it is likely that the applicant will lose his livelihood,

and - that risk would arise as a direct result of conviction and/or sentence, or through any other matter arising in the proceedings being decided against him (e.g. a condition of bail which the prosecution are seeking),

and - representation is justified in order to help the defendant avoid the conviction or the particular sentence (or other matter which may be decided against the applicant).

3. If the defendant is pleading guilty and must by law receive a sentence which is likely to lead to loss of livelihood then it is unlikely that he will qualify for grant. On the other hand, where the sentence likely to lead to loss of livelihood is discretionary and it can be shown that legal representation would assist in persuading the court to exercise its discretion in favour of the defendant, which the defendant would have difficulty achieving if unrepresented, then legal representation should be granted. Defendants intending to plead guilty need to be especially clear on the application form why legal representation would make a difference.

4. If a defendant will lose his job due to a driving ban, but he is pleading guilty to an offence carrying mandatory driving disqualification, then (in the absence of an argument for special reasons) legal aid is likely to be refused.

3.4 It is likely that I will suffer serious damage to my reputation

1. If the defendant is intending to plead guilty it is unlikely that an order will be granted under this heading as it is usually the conviction which gives rise to the damage and no lawyer could prevent this. This factor will therefore apply almost exclusively where the plea will be not guilty.

2. In every case two factors must be considered in deciding whether serious damage would be caused:

- the defendant’s current reputation, and

- the nature and seriousness of the offence.

3. The decision-maker then needs to consider the impact that conviction (or less likely, the sentence) would have on the defendant’s reputation and whether this could be said to be serious damage.

4. Case law10 suggests that any defendant of previous good character pleading not guilty to a charge equal to, or more significant than, section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986 in terms of nature and 10 R v. Chester Magistrates’ Court ex parte Ball, (1999) 163 JP 757.Interest of Justice guidance May 2018 18 seriousness should be granted legal aid, regardless of their social or professional standing. This is very unlikely to include non-imprisonable road traffic or regulatory offences.

5. There may be circumstances in which it is appropriate to grant legal aid under this heading to a defendant who has previous convictions. This will only arise where such convictions are either ‘spent’11, or are for minor offences that would not have been considered capable of causing serious damage to a defendant’s reputation (e.g. a defendant previously fined for careless driving is now contesting a charge involving dishonesty, or where the defendant has no similar convictions and the present offence is held in particular contempt). This means that even a defendant with a substantial record for imprisonable offences may be eligible if charged with a sexual offence.

10 R v. Chester Magistrates’ Court ex parte Ball, (1999) 163 JP 757

11 Under the terms of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974

3.5 Whether the determination of any matter in the proceedings may involve

consideration of a substantial question of law.

1. The applicant must identify:

- the question of law which may arise

- which aspect of the case it relates to (e.g. plea, trial etc)

- why it is substantial and beyond the remit of the duty solicitor.

2. Brief statements such as ‘recklessness’, ‘identification’, ‘intent’ etc are not acceptable without more information as it is possible that these issues turn entirely upon fact and not law.

3. If the applicant intends to plead guilty the likelihood of a substantial question of law arising must generally be remote. The need for a Newton hearing, special reasons hearing, or other sentencing considerations may complicate the sentencing process, but legal aid will be justified under this heading only if a substantial question of law may arise within them.

4. A right to representation should not generally be granted for the purpose of obtaining advice as to the appropriate plea, since this can rarely be described as a substantial question of law. Preliminary advice as to plea and routine questions of law can usually be provided satisfactorily by advice from the duty solicitor.

5. The substantial question of law will usually arise in cases where a trial is necessary. Substantial legal points may arise either before the trial (these could include applications for bad character, hearsay evidence to be adduced or where there is a statutory exception or defence) or during the trial itself.

6. The legal adviser is under a duty to advise magistrates openly in front of the defendant on any legal issues which arise. They are also obliged to assist an unrepresented defendant to present his case, but cannot represent him or argue a point of law for him.12

12 Practice Direction (criminal: consolidated). Criminal Procedure Rules 2010, Rule 37.14

Complex Areas of Law

7. The applicant should identify that there is an issue of law (rather than an issue of fact) and that this issue is complex. Supporting information will assist, as will reference to legal authority, whether that is statutory or case law.

8. Below are some common examples and what they ordinarily involve, this guide cannot cover every eventuality or legal point that may be raised. The table below gives a brief explanation of what the LAA may need to consider and the impact of this in proceedings. The LAA will consider the question of whether there is a complex area of law in the light of any additional representations made of the defendant’s ability to understand proceedings.

| What’s on the Application | Background Info | Impact on Legal Aid |

| R v Turnbull | Only relevant where the trial issue is identification. The case of R v Turnbull provides a checklist of criteria to consider in these cases due to the risk of wrongful conviction upon evidence of mistaken identity. The legal adviser should give a Turnbull direction at the conclusion of a trial in which ID is in issue but the identification evidence should be explored and challenged during cross examination of witnesses. Without representation this will be for the defendant to perform as it is beyond the role of the legal adviser to advocate on their behalf. | Unlikely a self‐represented defendant will have sufficient knowledge in this area. |

| Bad Character | An application can be made by the prosecution to include evidence of a defendant’s previous reprehensible behaviour. It can be opposed or unopposed and the legal adviser will advise the magistrates, in the presence of the defendant, the test set out in R v Hanson, R v Pickstone and R v Gilmore. Bad character can only be admitted through specific gateways and it will not be allowed into proceedings if it will render them unfair. The application from the prosecution is subject to timescales and is expected in a prescribed form as is the opposition, although this can be varied by the court and oral applications are allowed. Without representation the defendant can still oppose the application. Whether the defendant is represented or not, the test will be outlined by the legal adviser and applied by the Bench. Procedure can be explained to the defendant by the legal adviser. | Defendant can oppose this without representation and Court will have to apply a legal test before allowing previous convictions in anyway. Solicitor may assist in opposing an application but it is unlikely to be complex but that depends on the case specifics. |

| Special Measures | Similar to bad character insofar as the legal adviser will advise the Bench on law and procedure in the presence of the defendant. The direction to allow special measures is subject to a statutory test. The defendant can oppose any application without legal representation although its complexity may be elaborated upon within the application. Some special measures are automatic and require no representations (child witnesses for example). | Court must apply a statutory test anyway unless the witness is automatically entitled (e.g. a child). Can be opposed but can also be agreed. Solicitor may assist in opposing an application but it is unlikely to be complex, however the interests of a person other than the accused may be taken into account. |

| R v Galbraith No Case to Answer | Also called a half time submission, this application is made during a trial at the conclusion of the prosecution evidence where the case is so weak against the defendant that no reasonable tribunal could convict. Given the prosecution will serve evidence after the hearing when plea is taken it is difficult to foresee this argument arising early in proceedings. The prosecution are under a duty to review their case and should not proceed unless there is a realistic prospect of conviction in any event. These submissions are usually made as a result of poor or conflicting evidence at trial. R v Ivey R v Feely – Dishonesty – This is a legal test and difficulty could arise for someone who has limited knowledge of the law or generally. A legal adviser should give a direction at the conclusion of the trial and can explain to an unrepresented defendant what the test is prior to any trial and should do so if exploring the trial issues if dishonesty is identified as the issue for trial. | Unlikely to be identifiable until the day of trial. Prosecution do not have to serve all of their evidence at the first hearing anyway. Approach an application with caution on this ground. |

| R v Ivey, R v Feely Dishonesty | A legal test to be applied to establish if someone’s actions were dishonest. | A self‐represented defendant would have to be aware of the legal test for dishonesty rather than a layman’s interpretation. A solicitor would be able to advice on this and ask questions of the defendant to challenge the prosecution case. |

| Abuse of Process | Difficult to establish, abuse can rise where either the trial would be unfair (e.g. through delay or loss of evidence) or where it would be unfair for the accused to be tried (e.g. through misconduct on the part of the prosecution). If an abuse of process argument is viable, legal aid should be granted. Some outline of what is alleged to give rise to this would assist in evaluating the complexity and merits of such an application. As with the notes above for no case to answer, the prosecution are under a duty of what evidence they must serve and when to serve it. At the first hearing only the Initial Details are required, a charge, case summary, key statements and pre cons are usual. Further disclosure follows and is subject to rules and procedure. | Difficult to establish in reality. Insufficient evidence is unlikely to be enough as the prosecution are not under a duty to serve it all immediately. Applicants should have details of the actions of the prosecution giving rise to the abuse argument. |

| Actus Reus Mens Rea | Put simply they are the elements of a criminal offence. For example for theft – taking the property is the physical act or Actus Reus and the dishonest intention to deprive it from the owner is the guilty mind or Mens Rea. On the face of it not complex as it applies to the vast majority of criminal offences, legal doctrines and concepts are historically Latin. | They are not complex generally and apply to the majority of offences. With no additional information this means the defendant does not accept the offence so may just be a question of fact. |

| S76 & S78 PACE | Can be complex and surrounds unfairly obtained evidence being allowed into proceedings or admissions of guilt, gained through oppression being presented as evidence. Only relevant in relation to a contested matter but can be difficult for a self‐represented defendant to contend with. Some details of why the evidence is unfair will assist the LAA in evaluating this. | Can be complex and will usually require a solicitor to challenge police officers in relation to their interview techniques and compliance with statute and codes of practice. Admissibility of hearsay evidence is another category of admissibility which can raise complex issues as to whether the evidence is hearsay and, if so, whether it is admissible nonetheless. Applications should have some supporting information as to the nature of the application. |

| Exceptional hardship | Road traffic cases when a defendant puts forward an argument to avoid disqualification from driving. Common and procedurally straight forward. The Legal Adviser will assist with procedure and the test, the prosecution often won’t cross examine the defendant and there are no prosecution witnesses as the evidence is simply read to the court. | A straightforward test which a legal adviser will explain. Not usually difficult to understand and no prosecution witnesses required to give evidence. Rarely requires an advocate. |

| Special Reasons | Similar to exceptional hardship and if straight forward the defendant can deal with this issue. They differ to the extent that there may be prosecution witnesses, however and they can be a little more involved than exceptional hardship. Representations on the application should provide the nature of the special reason and any particular complexity. If the instruction of an expert witness is required then this will require representation. | Consider each on its merits, whether a defendant can act unrepresented. Any details of complexity should be in the application. Some SRs are more complex than others. For example where drink driving/failure to provide a specimen is concerned (i.e. laced drinks, shortness of distance driven or where witnesses are required). |

| Post Driving Consumption Hipflask defence | A defence to Excess Alcohol and generally it will require the instruction of a defence expert witness for a back-calculation report so is likely to require representation. | This will generally require an expert witness to provide a back- calculation report and will generally require representation. |

| Self Defence | Depends upon the understanding of the defendant generally. All the defendant has to do is raise self‐defence as an issue and the prosecution then have to disprove that assertion. While that may not be particularly complex of itself, further consideration should be given as to whether it is appropriate for the defendant to cross examine the injured party (see below) in such cases. | Defendant need only raise self‐defence and the prosecution have to prove otherwise. May not be particularly complex but there may be further consideration of whether it’s appropriate for the defendant to cross examine the victim, if so this should be an application of in the ‘interests of another’. |

3.6 I may not be able to understand the proceedings or present my own case

1. This criterion includes, but is not restricted to, cases in which the applicant has an inadequate understanding of English (or Welsh), and/or a disability. The length and complexity of the case is a relevant consideration in addition to the defendant’s level of understanding.

Inadequate Understanding of English

2. If English is not the applicant’s first language then the form should state the language the applicant normally speaks and the degree to which English can/cannot be understood and why this would make the proceedings too difficult for the defendant to deal with.

3. A need for an interpreter is not, in itself, sufficient to justify grant. Conversely, the provision of an interpreter does not necessarily mean that legal aid should be refused.13 It is important to consider other factors in the case which are relevant to the question of legal aid leaving aside the need for an interpreter. In the event that these other factors are not sufficient to justify grant the LAA must go on to consider the impact that the defendant’s lack of understanding of English would have on those other factors and on the wider case as a whole. This should include consideration of whether any pre-court documentation may be too lengthy or difficult for the applicant to deal with, and/or the need for a trial or Newton hearing.

13 In R (on the application of Luke Matara) v. Brent Magistrates’ Court (2005) 169 JP 576, it was held that, ‘The requirement that the proceedings be in a language that a defendant understood was merely one aspect of the requirement that a person must be able to effectively participate in criminal proceedings against him pursuant to the guarantee of a fair trial under the ECHR Article 6, and did not of itself negate the need for legal representation.’ The high court found that the applicant’s poor English undermined his ability to state his own case.

4. In order for legal aid to be granted there must be good reason why it would not be sufficient simply for the applicant to be provided with an interpreter, bearing in mind that it is not part of their role to give advice.

5. If the applicant speaks fluent English but the application is based upon a lack of literacy then the extent to which he is able to read and/or write must be stated, and the impact this would have on his ability to understand the proceedings or state his own case. The LAA should take into account the likely volume of pre-court documentation. A very strong presumption of grant should operate for applicants who are totally illiterate.

Disability

6. The fact that the applicant has a disability (whether physical or mental) is not sufficient in itself for legal aid to be granted. The question is what impact the disability would have on the applicant’s ability to understand the proceedings or to state his own case, and this should be stated on the application form.

7. General non-specific reference to a disability without confirmation or a diagnosis will not usually be sufficient. Whilst it will often not be necessary to have a detailed medical analysis of the condition said to be relevant there should be some supporting information e.g. ‘I was an in-patient at X hospital for six months last year’ or ‘I have been prescribed Y medication by my G.P. for my condition.’

8. For example it would not be sufficient to simply state ‘client has mental health problems’. Conversely an application that stated ‘client has severe learning difficulties which results in him being unable to read or write or understand the nature of the proceedings’ demonstrates that the IOJ test is met (see below for Youth clients).

Youths

9. The young age of the defendant may also be a relevant factor under this heading. See 3.9.7 in relation to youths below.

3.7 Witnesses may need to be traced or interviewed on my behalf

1. The application form should make clear:

- Who the witness is. (Not by name, but by their potential standing in relation to a possible matter in issue in the case).

- Whether the witness is known to the defendant.

- How their evidence could be relevant to an issue in the case.

- Why legal representation is necessary to trace and/or interview them.

2. Short statements such as ‘My brother-in-law’ or ‘There were other people with me in the car’ would not be adequate.

3. The fact that a defence witness is to be called is not in itself sufficient for legal aid to be granted under this heading unless pre-trial tracing or interviewing of that witness by a defence lawyer would be necessary in the interests of justice.14

14 In R v. Gravesend Magistrates’ Court ex parte Baker ((1997) 161 JP 765) the defendant was charged with excess alcohol and put forward a special reasons argument based on spiked drinks. The high court held that the applicant should be granted legal aid because a scientific expert would be required, the assistance of a solicitor would be needed to find witnesses of the facts, to take proper proofs, and to extract the story in the witness box from those witnesses and from the applicant herself. In R v. Scunthorpe Justices ex parte S (TLR 5 March 1998) the defendant (aged 16) was charged with obstructing a police officer in the execution of his duty. The high court held that in so far as there had been a conflict between the evidence of the police officer and witnesses, the applicant wanted the witnesses traced. A defendant aged 16 would be seriously handicapped if left to conduct his own defence and there was an obvious need for expert cross-examination.

3.7 The proceedings may involve the expert cross-examination of a prosecution witness (whether an expert or not)

1. This criterion is relevant only to those cases in which cross-examination of prosecution witnesses may be involved. This will include trials, special reasons hearings, and Newton hearings.

2. ‘Expert cross examination’ refers to the expertise required to-cross examine, and not the fact that a witness is an expert witness.

3. Not every cross-examination is an expert cross-examination calling for legal aid or representation. The decision whether to grant under this heading requires the LAA to think ahead to the trial and imagine what the cross-examination is likely to involve. The level of expertise needed will depend on a number of factors which will include:

- The nature and seriousness of the offence.

- The capacity of the defendant to cross-examine (including their age and understanding).

- The nature of the witness (police, expert, or other).

- The age and understanding of the witness.

- The relationship between the defendant and the witness.

- The number of witnesses.

- The issues in the case and their potential complexity.

- The issues that will need to be explored with the witness (i.e. the nature and extent of questions likely to be asked).

4. This is not an exhaustive list and the weight (if any) to be given to any single factor will vary from case to case. The fact that a witness is a police officer is a relevant consideration in favour of grant but is not, in itself, sufficient reason to grant.15

5. The LAA should take into account that legal advisers are under a duty to assist an unrepresented defendant and may ask questions of witnesses on the defendant’s behalf. They must not, however, appear to become an advocate for the defendant.16

6. Legal aid and representation will not be appropriate in the most straightforward of cases in which the issues are narrow and straightforward and few witnesses are to be called, and where the level of assistance afforded by the legal adviser would be adequate.

15 In R v. Scunthorpe Justices ex parte S (TLR 5 March 1998) the defendant, aged 16, pleaded not guilty to ‘obstruction’ on the basis that the police officer concerned was not acting in the execution of his duty. The High Court held that a defendant aged 16 would be seriously handicapped if left to conduct his own defence and there was an obvious need for an expert cross-examination.

16 Practice Direction (criminal: consolidated) para. V55.

3.8 It is in the interests of another person that I am represented

1. The other person will most commonly be a prosecution witness in cases of sensitivity where it would not be appropriate for the defendant to cross-examine them in person. A domestic abuse case requiring a trial or a Newton hearing is highly likely to qualify for grant.

2. If the person identified in the application is not a prosecution witness, then the LAA should consider very carefully what difference legal representation for the defendant will make to that person, particularly if they are not directly involved in the proceedings.

3. Relevant factors in relation to witnesses may include:

- the nature and seriousness of the charge,

- the relationship between the defendant and the witness,

- the vulnerability of the witness

- any issues of sensitivity which will need to be explored with the witness.

4. Examples of ‘another person’ outside the category of prosecution witnesses may include a co-defendant, or co-defendant’s witness in a sensitive case, particularly where there is a conflict of interest between co-defendants.

5. This is often in respect of the injured party and is often seen in violent, threatening or sexual offences, as well as circumstances of domestic abuse. If the issue is a guilty plea (without a Newton Hearing – a test of live evidence similar to a trial but upon a guilty plea rather than a not guilty plea) then the witness will not be called and the issue shouldn’t arise. If there is a Newton Hearing or a Not Guilty plea, however, it is inappropriate for the defendant to cross examine the witness. If Legal Aid is not granted, the court are under an obligation to instruct a solicitor to cross examine the witness on the defendant’s behalf in any event so representation is by and large appropriate where this witness is to be called.

6. This is not limited to domestic abuse cases, and would be similar if the witness is vulnerable for any other reason.

7. The question of representation being granted in the interests of the court is dealt with under ‘Any other reasons’ below.

3.9 Any other reasons

1. Other reasons may be taken into account as part of the interests of justice test beyond the criteria listed above. Additional factors may be sufficient in themselves to justify grant, but will usually be matters to be considered alongside other criteria in the application.

2. Examples in this category could include the need for expert examination of defence witnesses17 or expert cross-examination of a co-defendant or co-defendant’s witness.

17 R v. Gravesham Magistrates’ Court, ex parte Baker (1997) 161 JP 765

3. The likelihood of a demanding community penalty may be relevant, but will not in itself justify grant. (See comments made under the ‘Custodial Sentences’ heading above). There will need to be other relevant factors in the case which in combination with this would sufficiently justify legal representation.

4. All these are examples which have appeared in case law. Each case turns upon its own individual circumstances and combination of factors and it is very difficult to establish general rules about the weight that each factor should be given.

5. Where the defendant’s conduct of the case is such as to distract the court from the exercise of its judicial function it may be in the interests of justice for legal aid to be granted. (As in any other case, the grant of legal aid in these circumstances will still be subject to means testing). This is likely to occur only in exceptional circumstances and when the presence of a lawyer is justified in order to mitigate the problem. The defendant’s conduct of the case must be such as to obstruct the course of justice. Mere administrative inconvenience to the court would not be sufficient.

6. Situations may arise in which the court decides to exclude a disruptive defendant from the courtroom and proceed in his absence. Legal aid should not be granted merely because a defendant is drunk or disruptive.

Youth Cases

7. The Act makes no specific reference to youth defendants. The factors to be taken into consideration therefore apply equally to both youths and adults. As with adult cases, each application must be considered individually. Consideration of the defendant’s age is a factor to be taken into consideration, and a strong presumption of grant should operate for all defendants under the age of 16 on the basis that such defendants would be unable to understand the proceedings or to state their own case.

8. Loss of liberty will generally be less likely in youth cases. It should be remembered that the shortest custodial sentence available to a youth court is 4 months. Also, the younger the defendant, the less likely they are to be sent into custody for any given offence. These factors substantially diminish the importance of the ‘loss of liberty’ criterion in youth proceedings. Legal aid should only be granted under this heading on the basis of risk of a custodial sentence if, taking into account the defendant’s age as well as all other relevant factors, a custodial sentence of at least 4 months is likely.

9. Previous convictions should be taken into account in the same way as any other case in determining loss of liberty or any other factor.

10. Loss of liberty may also arise through a remand into custody or secure accommodation, although again this is less likely to occur in youth cases than adult cases. As in adult cases, the fact that the defendant appears in custody is not relevant. Legal Aid is justified only where it is likely that he will remain in custody after the hearing. If the risk of remand is relied upon, the application should state whether the prosecutor opposes bail.

11. While a youth is not entitled to automatic legal aid be aware of the fact that the younger a youth is, the less they are likely to understand and participate in proceedings. In particular where the defendant is under 16 there should be a strong presumption that legal aid should be granted as they would be

unable to understand proceedings or state their own case. Youth sentencing generally follows the guidelines for adults but the sentence is reduced dependent on age and understanding. The principal aim of the Youth Court is to prevent future offending, so sentencing may be geared towards intervention rather than punishment in appropriate cases. Applications to Vary or Discharge Orders

12. Criminal legal aid is available for proceedings in respect of a sentence or order which was made as a result of a conviction.18 Applications to vary or discharge such orders, including applications under section 42 Road Traffic Offenders Act 1988 to remove a driving disqualification, may therefore be granted.19

13. Whilst such proceedings are technically eligible for legal aid, a number of the usual criteria for grant will have no relevance at all and the great majority of cases will not satisfy the interests of justice test.20 Most applications of this nature will simply require the defendant to explain his circumstances to the court. Unless there is a clearly identifiable factor which takes the case outside the norm (e.g. a genuine need to obtain an expert report or a disability which would materially impair an applicant from explaining his circumstances to the court) legal aid should be refused.

18 Section 14 (b) Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of offenders Act 2012.

19 R v Liverpool Crown Court, ex parte McCann (1995) RTR 23.

20 R v Liverpool Crown Court, ex parte McCann (1995) RTR 23.

Community Penalties

14. The starting point is to ensure the offender complies with and completed the community order so breach should be dealt with by making the order more onerous. This can be by the addition of requirements to the order or the extension of those requirements in existence. Further breaches may be dealt with in this way and revocation and re‐sentence is ordinarily reserved for repeated breach. This may be sooner than expected if there is evidence of a wilful and persistent refusal to comply with an order, so beware of this. The commission of further offences while subject to a community order can mean that the order is re‐visited, but not necessarily and the order may often be left to run its course. This is particularly so if the new offence is less serious than the previous offence subject to the community order.

Suspended Sentence Orders

15. They are not community orders and the starting point upon breach is the immediate activation of the whole or part of the custodial term which has been suspended, plus a consecutive sentence for the new offence, if there is one (provided it can be punished with custody). The presumption is custody and only a finding that it is unjust to send the defendant to custody forthwith will allow them to remain at liberty. A breach of a suspended sentence order can arise from non‐compliance with requirements (similar to a community penalty breach) or by committing an offence while subject to the SSO. The court will take into account compliance with the order to date. A breach can be dealt with by imposing a fine so if it is a first and minor breach custody is not inevitable. If the breach is by way of commission of a new offence and that new offence is not imprisonable, case law suggests that activation of the suspended sentence is more unlikely.

Appeals

16. The interests of justice test applies to cases appealed to the Crown Court in the same way as any other case. If the test was not met in the magistrates’ court in the first instance it is very unlikely that it will be satisfied for the appeal case unless there has been a material and relevant change in circumstances (e.g. the defendant in fact received a custodial sentence when previously loss of liberty was deemed unlikely).

The Duty Solicitor

17. Where an application for a representation order has been refused and the solicitor named in that application is no longer acting on a defendant’s behalf, the defendant will still be entitled to see the duty solicitor provided that his case fulfils the criteria for the duty solicitor scheme. The mere fact that he has applied for and been refused a representation order does not render him ineligible for the duty solicitor.

ANNEX A

Prescribed Proceedings

S14 (h) of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act 2012 allows the Lord Chancellor to prescribe civil proceedings as being ‘criminal’ so that those cases may be funded under the criminal legal aid scheme instead of the civil legal aid scheme.

The list of civil proceedings which the Lord Chancellor has prescribed as criminal (‘prescribed proceedings’) are at regulation 9 of The Criminal Legal Aid (General) Regulations 2013.

These proceedings are criminal solely for the purposes of criminal legal aid funding, and so a client has to apply for a representation order in order to be represented with the benefit of legal aid.

Prescribed Proceedings in the magistrates’ court

Magistrates’ Court means testing applies to all criminal proceedings heard in the magistrates’ court (see regulation 9 of the Criminal legal aid (Financial Resources) Regulations 2013.

All prescribed proceedings in the magistrates’ court are subject to means testing and the usual processes for application and assessment apply.

The following proceedings are criminal proceedings for the purposes of section 9 of the Criminal Legal Aid (General) regulations 2013:

(a) civil proceedings in a magistrates’ court arising from a failure to pay a sum due or to obey an order of that court where such failure carries the risk of imprisonment;

(b) proceedings under sections 14B, 14D, 14G, 14H, 21B and 21D of the Football Spectators Act 1989(1) in relation to banning orders and references to a court;

(c) proceedings under section 5A of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997(2) in relation to restraining orders on acquittal;

(d) proceedings under sections 1, 1D and 4 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998(3) in relation to anti-social behaviour orders;

(e) proceedings under sections 1G and 1H of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998(4) in relation to intervention orders, in which an application for an anti-social behaviour order has been made;

(f) proceedings in relation to parenting orders made under section 8(1)(b) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998(1) where an order under section 22 of the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014(2) or a sexual harm prevention order under section 103A of the Sexual Offences Act 2003(3) is

made;

(g) proceedings under section 8(1)(c) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998(6) in relation to parenting orders made on the conviction of a child;

(h) proceedings under section 9(5) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 to discharge or vary a parenting order made as set out in sub-paragraph (f) or (g);

(i) proceedings under section 10 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998(7) in relation to an appeal against a parenting order made as set out in sub-paragraph (f) or (g)

(j) proceedings under Part 1A of Schedule 1 to the Powers of Criminal Courts (Sentencing) Act 2000(8) in relation to parenting orders for failure to comply with orders under section 20 of that Act;

(k) proceedings under sections 80, 82, 83 and 84 of the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 in relation to closure orders made under section 80(5)(a) of that Act where a person has engaged in, or is likely to engage in behaviour that constitutes a criminal offence on the premises;

(l) proceedings under sections 20, 22, 26 and 28 of the Anti-social Behaviour Act 2003(10) in relation to parenting orders—

(i) in cases of exclusion from school; or

(ii)in respect of criminal conduct and anti-social behaviour;

(m) proceedings under sections 97, 100 and 101 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003(11) in relation to notification orders and interim notification orders;

(n) proceedings under sections 103A, 103E, 103F and 103H of the Sexual Offences Act 2003(4) in relation to sexual harm prevention orders;

(o) Deleted;

(p) proceedings under sections 122A, 122D, 122E and 122G of the Sexual Offences Act 2003(5) in relation to sexual risk orders;

(q) Deleted;

(r) proceedings under section 13 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007(14) on appeal against a decision of the Upper Tribunal in proceedings in respect of—

(i)a decision of the Financial Services Authority;

(ii)a decision of the Bank of England; or

(iii)a decision of a person in relation to the assessment of any compensation or consideration under the Banking (Special Provisions) Act 2008(15) or the Banking Act 2009(16);

(s) proceedings before the Crown Court or the Court of Appeal in relation to serious crime prevention orders under sections 19, 20, 21 and 24 of the Serious Crime Act 2007(17);

(t) proceedings under sections 100, 101, 103, 104 and 106 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008(18) in relation to violent offender orders and interim violent offender orders;

(u) proceedings under sections 26, 27 and 29 of the Crime and Security Act 2010(19) in relation to—

(i)domestic violence protection notices; or

(ii)domestic violence protection orders; and

(v) any other proceedings that involve the determination of a criminal charge for the purposes of Article 6(1) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Prescribed Proceedings in the Crown Court

Applications for funding in ‘prescribed proceedings’ in the Crown Court is less straightforward. This is because, whilst most ‘prescribed proceedings’ fall within scope of the Crown Court means testing scheme (CCMT), a small number will not.

The different approach to ‘prescribed proceedings’ in the Crown Court is necessary because ,under Regulation 6 of the Criminal legal aid (Contribution Orders) Regulations 2013, CCMT only applies to criminal proceedings:

- in respect of an offence for which an individual may be, or has been, sent or committed by a magistrates’ court for trial at the Crown Court;

- which may be, or have been, transferred from a magistrates’ court for trial at the Crown Court

- in respect of which a bill of indictment has been preferred by virtue of section 2(2)(b) of the Administration of Justice (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1933(1); or

- Cases which are to be heard in the Crown Court following an order by the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court for a retrial.

Applying those criteria (and the usual provisions regarding criminal proceedings, such as the rule that representation orders for criminal proceedings cover preliminary or incidental proceedings), CCMT applies to all prescribed proceedings in the Crown Court other than those listed below (references to regulations are to references to regulations are to Criminal legal Aid (General) Regulations 2013):

(1) Regulation 9(f), as it applies to proceedings under section 8(1)(b) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 relating to parenting orders made in circumstances where a sexual offences prevention order has been made in respect of a child or young person under section 104 (2) and (3) of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (order following conviction etc for a listed offence). CCMT would not apply to a parent who applies for a representation order in respect of such proceedings;

(2) 9(g), as it applies to proceedings under section 8(1)(c) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 relating to parenting orders made on the conviction of a child or young person for an offence in the Crown Court. CCMT would not apply to a parent who applies for a representation order in respect of such proceedings;

(3) Regulation 9(h), as it applies to an application to vary or discharge a Parenting Order made as in proceedings described in paragraphs (1) and (2) above.

(4) Regulation 9(s), as it applies to:

I. an order made under section 19 of the Serious Crime Act 2007 in respect of a person within section 19(1)(a) (Serious Crime Prevention Order made against a person committed for sentence to the Crown Court).

II. variation of a Serious Crime Prevention Order pursuant to 20 of the Serious Crime Act 2007 in respect of a person within section 20(1)(a) (a person committed for sentence to the Crown Court).

III. variation of a Serious Crime Prevention Order pursuant to section 21 of the Serious Crime Act 2007 in respect of a person within section 21(1)(a) (a person convicted of an offence in the magistrates court under section 25 of the 2007 Act who is committed for sentence to the Crown Court).

CCMT does not of course apply to any prescribed proceedings that do not take place in the Crown Court, So, for example, CCMT does not apply to proceedings under Regulation 9 (a) of Criminal legal aid (General) Regulations 2013 (civil proceedings in the magistrates court arising from failure to pay a sum due etc).

CCMT also applies to appeals to the Crown Court in respect of matters disposed of in the magistrates’ court (Regulation 40 of Criminal legal aid (Contribution Orders) Regulations 2013).

Where the prescribed proceedings follow from ordinary criminal proceedings in the Crown Court (so that they are part of those proceedings or incidental to them) and a representation order is already in place in respect of the main proceedings, that representation order will cover the prescribed proceedings. In such cases, CCMT will already have been applied at the point of the original application for the representation order and no new legal aid application (or CCMT assessment) is required.

NOTE: Where no representation order is in place for the main proceedings, the availability of public funding for any subsequent prescribed proceedings heard before the Crown Court will require a fresh legal aid application. This should be submitted in the normal way through the magistrates’ court. The application will be subject to the IoJ test, and in light of the guidance outlined above, may also be subject to CCMT.